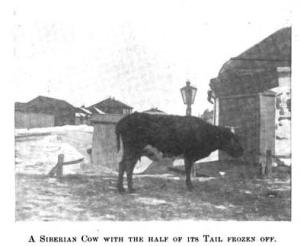

Three letters dispatched from the Siberian city of Chita appeared in the February 14, 1920 issue of Soviet Russia: A Weekly Devoted to the Spread of Truth About Russia. Re-printed by the editor for their “rather interesting data concerning conditions in Siberia,” the letters paint a bleak but intriguing picture of life on the tundra.

The correspondent opens the first letter with a stoical weather report. “The temperature at present is 35 below zero,” he writes, “Last year’s coldest was 85 below zero. You find pigeons and sparrows lying dead in the streets where they fell frozen.” The relentless hyperborean cold struck down not only birds. “Human beings also have been found frozen to death in the streets,” he continues. “The poor, on finding the bodies, remove the clothing and put it on themselves. The naked bodies have been devoured by dogs, and now present a terrible sight.”

Continue reading